New York

뉴욕

2002년 설립 이래, 로렌스 그레서 (Lawrence T. Gresser) 대표 변호사가 이끌고 있는 뉴욕 사무소는 소송 및 중재, 지적 재산권 및 테크놀로지, 화이트 칼라 디펜스, 기업 거래 및 자문 등의 전문 분야를 토대로, 60여명의 변호사를 보유한 중형 로펌으로 빠르게 성장하였습니다.

저희 뉴욕 사무소는 특히 증권 관련 소송 및 중재, 국제 중재, 규제 조사 (regulatory investigations), 특허 소송, 기업 인수 합병 분야에 두각을 나타내왔습니다. 또한 미국 뿐만 아니라 전 세계에 걸쳐 법률 서비스를 제공하고 있으며, 미국, 유럽, 아시아, 호주 등의 주요 금융 기관과 포춘 500 기업 고객들을 대리하여 복잡한 소송, 조사, 거래와 관련한 다양한 법률 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다. 저희 뉴욕 사무소 소속 변호사들은 체임버스 USA, 리걸 500, 벤치마크 리티게이션 등의 기관에서 인정 받았으며, 미국에 기반을 두고 있는 변호사의 반이상은 슈퍼 번호사와 떠오르는 스타 변호사로 인정 받았습니다.

저희 뉴욕 사무소 소속 변호사들은 서울과 파리 그리고 워싱턴 D.C 사무소의 변호사들과 긴밀하게 협조하여 국제 소송, 규제 조사 및 국제 거래와 관련한 법률 서비스를 제공하고 있으며, 미국에서 비즈니스를 하는 해외 고객을 대리하여 다양한 법규 및 규제에 관한 자문 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.

Legal 500 US Elite spotlights top lawyers at regional firms across key U.S. business centers. The rankings identify attorneys handling market-leading work at the highest level in their respective cities.

Legal 500’s rigorous selection process includes interviews with leading practitioners, peer and client feedback, and a review of key matters handled over the past year. Legal 500’s in-depth research ensures that only the most accomplished attorneys are recognized.

Congratulations to Larry and Mark on this well-deserved honor.

Cohen & Gresser partners Christian R. Everdell and Sri Kuehnlenz examine how the nomination of Jay Clayton as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York could shape the office’s enforcement priorities in a new article published by Law360. The piece explores anticipated areas of focus and the potential implications for white-collar enforcement and corporate investigations.

Read the full article on Law360 here (subscription required).

Mark is recognized for White Collar and Litigation, and Larry is recognized for Litigaton.

This year marks the 20th edition of Lawdragon’s flagship guide—an “ode to the greatest lawyers in the greatest legal system in the world.” Lawdragon performs an extensive review of submissions to identify lawyers who have demonstrated unparalleled skill, dedication, and leadership in shaping the legal landscape.

Mark and Larry were also recognized in the 2025 Lawdragon “500 Leading Litigators in America” guide, which was released in September.

"We are proud to congratulate Sri, Drew, Christine, and Saruji on their well-earned promotions," said Lawrence T. Gresser, the firm’s global managing partner. “They are superb lawyers and wonderful people. We are lucky to have them, and we are excited to see their continued success at Cohen & Gresser.”

Sri Kuehnlenz – Partner, New York

Sri Kuehnlenz is a member of the firm’s Litigation & Arbitration and White Collar Defense & Regulation groups. She represents companies and individuals in complex matters involving contract disputes, securities laws, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, consumer protection laws, and executive employment issues, with a focus on complex financial and accounting cases. Her notable work includes representing the defendant in a high-profile five-week criminal jury trial in the cryptocurrency sector, defending a major credit card corporation against a deceptive practices claim, defending an asset management firm against contract, tort, and statutory claims arising from a complex financial arrangement, and handling a pivotal breach of contract appeal for a hedge fund. Sri also advises clients on pre-litigation strategy and employment negotiations. Recognized as a Rising Star by Law360 in 2024 and by Super Lawyers since 2019, Sri is a trusted advocate in high-stakes litigation and regulatory matters.

Drew S. Dean – Counsel, New York

Drew S. Dean is a trusted advocate in high-stakes commercial litigation and white-collar defense matters, representing clients in sensitive and often multi-jurisdictional disputes. In addition to his litigation practice, Drew advises clients on domestic and international strategic investments, mergers and acquisitions, and a wide range of corporate transactions. His exceptional legal work and dedication to client service have earned him recognition as a Super Lawyers Rising Star every year since 2020.

Christine M. Jordan – Counsel, New York

Christine M. Jordan has extensive experience representing corporations, financial institutions, and individuals in high-stakes litigation before federal and state courts, as well as in arbitral tribunals. Christine’s practice spans a wide range of complex disputes, including those involving mergers and acquisitions, securities, contracts, real estate, and bankruptcy. Christine has been recognized by Super Lawyers as a Rising Star for general litigation every year since 2022.

Saruji Sambukumaran – Counsel, Paris

Saruji Sambukumaran focuses on all aspects of French employment law (legal counseling and assistance in transactional and litigation matters) including individual and collective relations. With a deep understanding of the complexities of French labor regulations and workplace dynamics, she advises both domestic and international clients on a wide range of employment matters, notably compliance, workforce management, reorganization and redundancy matters, trade union and representative body relations, and dispute resolution.

The ideological battle over the role of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investment standards intensified last week, as the Texas Attorney General and 10 other Attorneys General sued three asset management companies, alleging that ESG strategies pursued by these companies in relation to coal production violated federal and state antitrust laws.

ESG is a set of standards or ideals that socially conscious investors seek out when choosing where to place their money. Over the past four years, ESG investment standards have become increasingly controversial. Some liberal and progressive advocates have sought to pressure large investors to consider issues such as racial justice, labor policies, and environmental stewardship when making investments in companies. At the same time, some conservative critics have opposed ESG as an attempt to inject ideology into investment decisions at the expense of shareholder value.

Allegations and Defenses

The tension is on full display in the Texas complaint. The complaint alleges that the three asset management companies—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—violated Section 7 of the Clayton Act by acquiring minority interests in multiple competing coal-producing companies and then using governance rights (such as proxy votes) to influence the coal companies to reduce output in the name of environmental stewardship. The complaint alleges that this output reduction, in turn, raised the price of coal directly and consumer electric bills indirectly. The states claim that the agreement was reached through organizations committed to reducing carbon output, such as Climate Action 100+ and the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative.

The investment firms likely will raise several defenses. Among other things, they likely will argue that the states have not plausibly alleged an agreement among the investment companies. The complaint relies heavily on public statements and on the involvement of the investment companies in industry organizations, but the law imposes a high pleading burden on Section 1 plaintiffs, and the absence of a plausible economic motive may prove problematic for the plaintiffs. The companies will likely also challenge the plaintiffs’ allegations of anticompetitive effect. The plaintiffs appear to allege that the agreement had the effect of increasing the price of coal, but given the nature of the alleged agreement, if proven, it likely would be assessed under the Rule of Reason. This means the alleged agreement’s pro-competitive justifications (disregarding any potential environmental benefits) would be weighed against the anti-competitive effects, and these types of cases are often difficult for plaintiffs to prove.

Similarly, the complaint’s Section 7 challenge to the acquisition of a minority interest by different investors in different coal companies may be difficult to prove. The companies will likely point out that the investors are not alleged to have controlled any of the acquired companies, either individually or collectively, and if accepted, the claims would represent an expansion of the antitrust laws. Under either claim, any economic analysis of a but-for world would be complicated by competing industry trends and regulations.

Broader Implications for ESG and Antitrust

Certainly, it is possible to imagine ESG efforts that would raise significant antitrust concerns, given that ESG goals often require industry collaboration. Notwithstanding the best intentions, case law has held that an effort to achieve social good through collusion or unlawful agreements does not provide a defense, let alone immunity, to an antitrust challenge. Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679 (1978) (rejecting the argument that safety concerns justified an agreement among engineers not to quote prices before being hired); In Re Processed Egg Prod. Antitrust Litig., 851 F. Supp. 2d 867, 877 (E.D. Pa. 2012) (industry agreement to improve the quality of life for animals may be alleged to increase prices or reduce output).

Government regulation may be an answer when an industry-wide agreement is needed to achieve a societal goal, but it is an imperfect one. The Noerr-Pennington doctrine holds that anticompetitive effects caused by petitioning the government are immune from antitrust liability. The state action doctrine holds that state actors, including state regulatory boards dominated by industry participants, are generally not subject to antitrust scrutiny. A regulator may choose standards that are not ideal for the industry, and unlike voluntary standards, companies cannot opt out of government-enforced regulations.

The heightened scrutiny of ESG means that any ESG effort must be approached with great care and sensitivity toward antitrust. Trade organizations can be alleged to be conduits for sharing sensitive information, and statements about intentions to adhere to policies or standards can be interpreted as signals or invitations to collude, even when made publicly. Accordingly, the compliance rules applicable to trade associations and public announcements of intentions should be observed diligently when the topic is ESG.

Conclusion: A Case to Watch

Finally, while ESG aspirations have not yet been tested as a defense to antitrust claims, there is no basis in antitrust law for targeting ESG goals as inherently suspect or deserving of greater antitrust scrutiny than other industry self-regulatory efforts. Given the controversial nature of ESG, this case will certainly be followed closely.

The GIR 100, a definitive guide to the world’s top firms for investigations, recognized Cohen & Gresser for its exceptional representation of high-profile individuals and companies. The firm was highlighted for its strong team of renowned lawyers operating in key jurisdictions worldwide. The GIR 100 is based on comprehensive submissions and rigorous independent research, identifying the top 100 firms globally that excel in government-led, internal, and cross-border investigations.

Cohen & Gresser’s White Collar Defense and Regulation practice, which spans its offices in New York, Washington, D.C., Paris, and London, is central to its continued success. The practice boasts a highly experienced Internal Investigations team that advises global clients, including corporations, boards of directors, special committees, and audit committees.

The team’s work encompasses the full spectrum of investigations, from responding to discrete, anonymous employee complaints to managing complex, wide-ranging investigations tied to ongoing litigation or regulatory and criminal scrutiny.

This recognition underscores Cohen & Gresser’s dedication to providing clients with sophisticated, strategic counsel in even the most challenging investigative matters.

Mansfield Certification is a year-long, structured certification process designed to ensure that all qualified talent at participating law firms has a fair and equal opportunity to be considered for leadership roles. The focus is on widening the pool of candidates for leadership positions and ensuring transparent, inclusive advancement processes. By requiring that at least 30% of talent considered for leadership roles consists of underrepresented groups, Mansfield Certification creates a more level playing field for all.

“Diversity, equity, and inclusion are not just values we talk about; they are integral to how we operate as a firm,” said Lawrence T. Gresser, the firm’s managing partner. “Achieving Mansfield Certification is a natural extension of our ongoing efforts to ensure that our leadership and decision-making structures reflect diverse perspectives and backgrounds. While we recognize there is more work to be done, we remain dedicated to making meaningful progress that benefits both our firm and the legal profession.”

Cohen & Gresser is deeply committed to fostering a workplace where every individual feels valued, supported, and empowered to succeed. The firm has taken meaningful steps to promote diversity and inclusion within the organization and across the legal community.

“Achieving Mansfield Certification reflects our commitment to making lasting changes within the firm,” said partner Karen Bromberg, co-lead of Cohen & Gresser’s Mansfield 2023-2024 initiative. “We believe that fostering a workplace where everyone has the opportunity to succeed strengthens our ability to serve our clients and communities. We are excited to continue this journey and look forward to the positive impact it will have on our firm, clients, and the broader community.”

By earning Mansfield Certification, Cohen & Gresser joins a distinguished group of over 360 certified law firms nationwide that are setting a new standard for diversity and inclusion, reinforcing the core value that everyone should have a fair opportunity for career advancement.

“The firm has renewed its commitment to the certification process for the 2024-2025 period, and will continue to track its progress to ensure these efforts lead to meaningful, sustainable change,” added Heather Kelly, the firm’s chief operating officer and co-lead of the Mansfield initiative.

For more information about Cohen & Gresser’s Mansfield Certification, please contact MansfieldWC@cohengresser.com.

The “Stars” featured in the guide are recognized through Benchmark Litigation’s independent research as some of the foremost litigation practitioners in the United States. The selection process involves in-depth interviews with litigators, dispute resolution experts, and their clients, along with a thorough review of significant cases and firm developments. Lawyers named as “Stars” are highly respected by their peers and stand out for their impressive case track records and positive client feedback.

Since its inception in 2008, Benchmark Litigation has been the only publication on the market to focus exclusively on litigation in the United States.

With over 20 years of experience in legal technology and innovation, Pere brings a wealth of expertise in designing and implementing cutting-edge solutions that optimize client outcomes and operational efficiency. He has played a pivotal role in advancing Cohen & Gresser’s technology over the past six years, particularly in the integration of machine learning for complex data analysis. His expertise in leveraging AI-driven tools has enabled the firm to streamline Big Data litigation and investigations, delivering more precise insights and improved outcomes for our clients.

“We are excited to have Pere step into this key leadership role,” said Lawrence T. Gresser, Cohen & Gresser’s Managing Partner. “His vision and expertise will be critical in advancing our commitment to innovation, enabling us to provide even better service and results for our clients. Pere’s appointment underscores our dedication to continually improving efficiency and staying ahead in an evolving legal landscape.”

“I am thrilled to take on the role of Global CIO and lead the firm’s innovation efforts,” said Pere Puig Folch. “Our goal is to ensure that our technology and processes not only meet but exceed the demands of our clients and the industry. I look forward to collaborating with our talented team to drive meaningful change across all our offices.”

Pere’s appointment reinforces Cohen & Gresser’s commitment to adopting the latest innovations in legal technology and process management, ensuring the firm remains a leader in delivering top-tier results to clients worldwide.

Press

Cohen & Gresser Appoints Data Director As Global CIO, Law360 (Oct. 30, 2024)

View All

General Inquiries

info@cohengresser.comManaging Partner

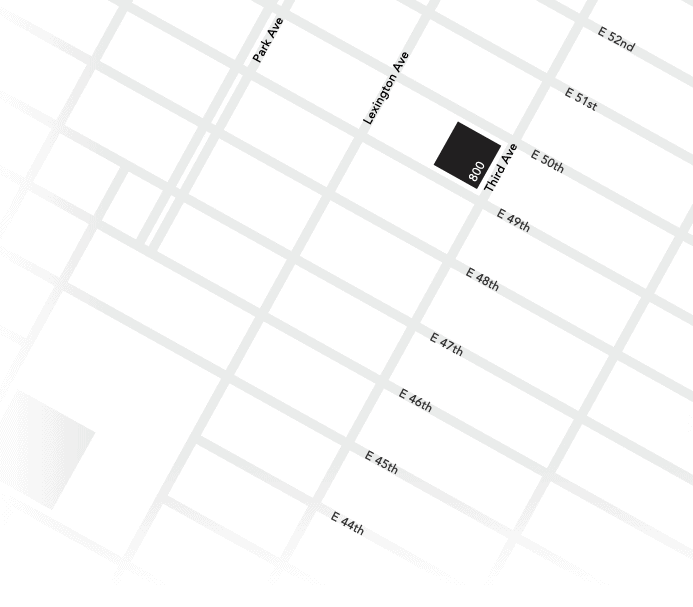

Mark S. Cohen800 Third Avenue New York, NY 10022

+1 212 957 7600 phone +1 212 957 4514 fax