Washington, D.C.

At Cohen & Gresser, our Washington, D.C. office specializes in a broad range of commercial litigation and regulatory enforcement actions, with a particular emphasis on both domestic and international antitrust and complex litigation matters. Our experienced attorneys provide comprehensive advice on all facets of U.S. antitrust law, encompassing both criminal and civil litigation, as well as compliance and regulatory issues before federal agencies. Additionally, we adeptly manage a variety of other commercial litigation cases throughout the DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia) area.

Leading our Washington, D.C. office is Melissa H. Maxman, a distinguished partner with three decades of experience in advising domestic and international corporations on global antitrust and related business issues. She is admitted to practice law in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, bringing a wealth of experience and a commitment to excellence in every case she oversees.

Congratulations to:

- Melissa H. Maxman and Ronald F. Wick, named 2025 Washington, D.C. Super Lawyers for Antitrust Litigation

- Derek Jackson and Alisa Lu, recognized as 2025 Washington, D.C. Rising Stars for Business Litigation

Each year, Super Lawyers identifies outstanding lawyers nationwide and regionally who have attained a high degree of peer recognition and professional achievement. Only 5 percent of lawyers are selected as Super Lawyers, and only 2.5 percent are selected as Rising Stars.

Ribera drives Europe's Green Deal goals by overseeing the Clean Industrial Deal, advancing clean tech investment, decarbonizing the economy, reducing energy prices, ending fossil fuel dependency, and tackling energy poverty.

Their conversation explored the future of sustainable innovation and the policies shaping a cleaner, more equitable, and competitive global economy.

The Little Tech Competition Summit is an initiative by Y Combinator, a renowned startup accelerator, aimed at advocating for and supporting emerging technology companies

Press:

EU’s Teresa Ribera Looks to Thread the Trans-Atlantic Needle on the DMA

In an episode of the ABA Antitrust Law Section’s podcast, Our Curious Amalgam, Derek Jackson co-hosted a discussion on recent investigations by European regulators into AI companies.

Tune in to this episode to gain insights into the analysis of AI under the GDPR and the challenges European regulators are facing.

One of the six landlords has agreed to a settlement that, if approved, would prohibit it from using competitors’ non-public information to run or train its pricing models, and from using third-party pricing software or algorithms without the supervision of a court-appointed monitor. The settlement also requires the landlord’s cooperation in the litigation.

The new allegations against landlords in the RealPage suit add another dimension to the collection of algorithmic price-setting cases that have developed in recent years, including private litigation against RealPage. Collectively, these cases have begun to shape the early contours of the answer to an important question: To what extent does algorithmic price-setting constitute unlawful price-fixing in violation of the Sherman Act?

Instructing the Algorithm: The Topkins Prosecution

In 2015, in United States v. Topkins, the DOJ brought its first criminal prosecution targeting the use of algorithmic price fixing. The DOJ entered into a plea agreement with a former e-commerce executive stemming from his participation in an alleged price-fixing conspiracy involving the sale of posters on Amazon’s marketplace. The DOJ alleged that the executive and his co-conspirators agreed to adopt specific algorithms for the sale of the agreed-upon posters with the goal of coordinating price changes, and that the executive wrote computer code that instructed his company’s algorithm-based software to set prices of the agreed-upon posters in conformity with the agreement. Topkins heralded a new era in enforcing antitrust laws in the realm of algorithmic pricing.

Topkins involved conspirators communicating directly about algorithmic pricing and directly instructing the pricing algorithms, resulting in anticompetitive effects in the marketplace. The fact pattern in Topkins, while in the context of algorithmic pricing, involved conduct that would constitute a traditional Sherman Act violation: direct instruction of the algorithm and communications among conspirators, a prohibited agreement in restraint of trade.

Post-Topkins cases, however, have been more nuanced. Rather than directly instruct an algorithm to conform to a price-fixing agreement, the more recent cases involve competitors feeding their non-public information to a third-party algorithm that uses the information to make pricing recommendations. Under this scenario, the lawfulness of the conduct may turn, at least in part, on the extent to which there is an agreement or expectation that competitors’ prices will follow the platform’s model, as well as whether the software algorithm bases its recommendations on competitors’ non-public information. What remains to be seen is whether an algorithmic price-setting machine learning model that “learns” to set prices based on competitively sensitive information received from multiple competitors can ever be lawful, and if so, under what circumstances.

“Mandatory” Price Recommendations

The RealPage cases involve competitors providing data to a software algorithm that then recommends prices to its users—recommendations that allegedly border on mandates. The DOJ complaint alleges that RealPage’s products make it easy for property managers to accept its recommendations, such as through “bulk” acceptances, but difficult and time-consuming to decline them. In their statements of interest filed in ongoing private litigation against RealPage, the DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) argued that real estate owners and operators, after sending RealPage their nonpublic and competitively sensitive data, “overwhelmingly priced their units in line with RealPage’s suggested prices (80-90%).” In doing so, the agencies argued, owners/operators effectively delegated independent decision-making to the algorithm, and RealPage prevented deviations from its suggested prices by enforcing and monitoring compliance with those prices.

In the private litigation, a Tennessee federal court denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss the complaint, finding that the plaintiff lessees had adequately alleged parallel conduct through the defendants’ change in pricing strategies following their adoption of RealPage’s software—including price increases during an economic downturn that were against the defendants’ self-interest. This finding would appear to be consistent with the allegation that RealPage’s users have little discretion to override the algorithm’s recommendations.

Similarly, in Duffy v. Yardi Systems, Inc., a Washington federal court, in December, denied a motion to dismiss based on similar allegations, also involving pricing algorithms in the multifamily housing market. In Duffy, however, the court neither required nor cited any allegations as to the mandatory nature of the price recommendations. Instead, the court relied on allegations from which it could infer that each lessor contracted with the software maker “in circumstances showing an intent to participate in a concerted scheme or plan to fix rental prices and restrain trade.” According to the court, the complaint alleged that the software provider advertised its product “as a means of increasing rates above those available in a competitive market.” It also alleged that “[e]xisting lessor clients publicly touted the success of Yardi’s efforts to increase rental rates, the benefits of not having to guess at market conditions or to offer concessions/specials, and the elimination of concerns that they would be underbid, implicitly inviting other lessors to sign up and enjoy the same benefits.” The court rejected the argument that the complaint was required to allege a specific agreement to implement the algorithm’s pricing recommendations, finding that “the allegations amply suggest that the lessors intended to, and for the most part, did adhere” to the recommendations.

The DOJ/states’ amended complaint in RealPage goes even further. Rather than rely solely on each landlord’s independent agreement with RealPage, the DOJ/states allege traditional Section 1 conduct between the landlords, including sharing of pricing and occupancy information, information about a particular landlord’s acceptance of RealPage’s recommendations, and the parameters applied by a particular landlord in using the software’s “auto-accept” feature. These allegations provide an element often found lacking in a “hub and spoke” conspiracy: a rim connecting the spokes.

Software Algorithms Recommending—Not Mandating—Prices to Users

A different outcome was reached in Gibson v. Cendyn Group, LLC, where an algorithm’s price recommendations were not followed as consistently. In June 2024, a Nevada federal court dismissed a putative consumer class action alleging that Las Vegas hotel operators unlawfully delegated independent decision-making to a software algorithm, which then recommended prices for hotel rooms based on public information regarding competitors’ pricing. The court held that the plaintiffs had failed to plausibly allege a tacit agreement among the hotels because the hotels “are not required to and often do not accept the pricing recommendations generated by” the algorithm.

Like the court in the private RealPage litigation, the court in Gibson focused on the extent to which the algorithm’s pricing recommendations were alleged to be mandatory. In Gibson, however, the court found they were not. Therefore, the court reasoned, “[i]t accordingly cannot be that the vertical arrangements between Cendyn and Hotel Defendants to license GuestRev and GroupRev restrain trade.”

But discretion was not the only factor considered in Gibson. In addition to the non-mandatory nature of the price recommendations, the court in Gibson also noted that the price recommendations were based on publicly available information, stating that “consulting your competitors’ public rates to determine how to price your hotel room—without more—does not violate the Sherman Act.” The plaintiffs argued that even if confidential information was not exchanged directly between competitors, their allegations created an inference that the algorithms improved over time by running on confidential information provided by each of the competitors. The court held, however, that even if this occurred, it would not constitute a tacit agreement to fix prices.

In September 2024, a federal court in New Jersey similarly dismissed with prejudice a complaint brought by putative class action plaintiffs against owners and operators of various Atlantic City casino-hotels. In Cornish-Adebiyi v. Caesars Entertainment, Inc., the court rejected the plaintiffs’ allegation that casino-hotels engaged in a conspiracy to artificially fix prices through their “knowing and purposeful shared use” of the algorithmic software. In addition to the pricing authority that the hotels “continued to retain and exercise,” the court found that the plaintiffs failed to allege an illegal price-fixing conspiracy through the “knowing” and “purposeful” use of the software algorithm. The court cited the absence of any allegation that the hotels’ “proprietary data are pooled or otherwise comingled into a common dataset against which the algorithm runs.” In other words, the court concluded, “the pricing recommendations offered to each Casino-Hotel individually are not based on a pool of confidential competitor data.”

Both Gibson and Cornish-Adebiyi suggest that there may be no Sherman Act violation unless the algorithm pools competitors’ non-public information in making its recommendations. Both cases, however, are now pending appeal to the Ninth and Third Circuits, respectively. These courts are poised to become the first federal appellate courts to weigh in on algorithmic price-setting, and their decisions may provide more robust guidance.

Other courts may reach different conclusions from those reached to date. But collectively, the decisions to date suggest, at a minimum, that liability may follow where (i) adoption of most or all of an algorithm’s pricing recommendations is mandatory or agreed among users or (ii) the algorithm pools its users’ non-public information in making pricing recommendations. What is less clear is the permissibility of the use of confidential information merely to train the algorithm.

FTC and DOJ View: Price Discretion Does Not Doom Algorithmic Price Fixing Claim

The enforcement agencies, in their statements of interest filed in the private cases, have taken a less nuanced position: that algorithmic pricing is a per se violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act, and there is no limitation simply because the recommended prices are non-binding. The FTC and DOJ have argued that the violation is the agreement itself, and that the frequency with which the agreement is followed is irrelevant. In their view, the competitors’ retention of price discretion does not doom a price-fixing claim. They liken the algorithmic price to an agreement to fix advertised list prices, arguing that such an agreement would be unlawful even if the conspirators sometimes deviate from the list price—and that the use of recommendations from a common algorithm is similarly unlawful. It remains to be seen whether the agencies will continue to take such a forceful position under the Trump Administration.

Conclusion

With the upcoming appeals in Gibson and Cornish-Adebiyi, two federal appellate courts may weigh in on algorithmic price fixing sometime this year. Even with such rulings, however, the larger question will remain: whether algorithms—which, using artificial intelligence, can learn from experience and experimentation—are capable of tacitly colluding absent any active participation, express agreement, or even an invitation and subsequent participation from competing firms. While Sherman Act Section 1 violations have long required a meeting of human minds, courts are about to find themselves in the position of applying Section 1 to non-sentient artificial intelligence models that can learn to collude with minimal, if any, human intervention.

This prestigious recognition highlights their exceptional expertise and commitment to excellence in navigating the complex antitrust and competition landscape.

Melissa and Ron were also recognized in the 2025 Lawdragon “500 Leading Litigators in America” guide, which was released in September.

Congratulations to Melissa and Ron on this well-deserved honor.

The ideological battle over the role of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investment standards intensified last week, as the Texas Attorney General and 10 other Attorneys General sued three asset management companies, alleging that ESG strategies pursued by these companies in relation to coal production violated federal and state antitrust laws.

ESG is a set of standards or ideals that socially conscious investors seek out when choosing where to place their money. Over the past four years, ESG investment standards have become increasingly controversial. Some liberal and progressive advocates have sought to pressure large investors to consider issues such as racial justice, labor policies, and environmental stewardship when making investments in companies. At the same time, some conservative critics have opposed ESG as an attempt to inject ideology into investment decisions at the expense of shareholder value.

Allegations and Defenses

The tension is on full display in the Texas complaint. The complaint alleges that the three asset management companies—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—violated Section 7 of the Clayton Act by acquiring minority interests in multiple competing coal-producing companies and then using governance rights (such as proxy votes) to influence the coal companies to reduce output in the name of environmental stewardship. The complaint alleges that this output reduction, in turn, raised the price of coal directly and consumer electric bills indirectly. The states claim that the agreement was reached through organizations committed to reducing carbon output, such as Climate Action 100+ and the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative.

The investment firms likely will raise several defenses. Among other things, they likely will argue that the states have not plausibly alleged an agreement among the investment companies. The complaint relies heavily on public statements and on the involvement of the investment companies in industry organizations, but the law imposes a high pleading burden on Section 1 plaintiffs, and the absence of a plausible economic motive may prove problematic for the plaintiffs. The companies will likely also challenge the plaintiffs’ allegations of anticompetitive effect. The plaintiffs appear to allege that the agreement had the effect of increasing the price of coal, but given the nature of the alleged agreement, if proven, it likely would be assessed under the Rule of Reason. This means the alleged agreement’s pro-competitive justifications (disregarding any potential environmental benefits) would be weighed against the anti-competitive effects, and these types of cases are often difficult for plaintiffs to prove.

Similarly, the complaint’s Section 7 challenge to the acquisition of a minority interest by different investors in different coal companies may be difficult to prove. The companies will likely point out that the investors are not alleged to have controlled any of the acquired companies, either individually or collectively, and if accepted, the claims would represent an expansion of the antitrust laws. Under either claim, any economic analysis of a but-for world would be complicated by competing industry trends and regulations.

Broader Implications for ESG and Antitrust

Certainly, it is possible to imagine ESG efforts that would raise significant antitrust concerns, given that ESG goals often require industry collaboration. Notwithstanding the best intentions, case law has held that an effort to achieve social good through collusion or unlawful agreements does not provide a defense, let alone immunity, to an antitrust challenge. Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679 (1978) (rejecting the argument that safety concerns justified an agreement among engineers not to quote prices before being hired); In Re Processed Egg Prod. Antitrust Litig., 851 F. Supp. 2d 867, 877 (E.D. Pa. 2012) (industry agreement to improve the quality of life for animals may be alleged to increase prices or reduce output).

Government regulation may be an answer when an industry-wide agreement is needed to achieve a societal goal, but it is an imperfect one. The Noerr-Pennington doctrine holds that anticompetitive effects caused by petitioning the government are immune from antitrust liability. The state action doctrine holds that state actors, including state regulatory boards dominated by industry participants, are generally not subject to antitrust scrutiny. A regulator may choose standards that are not ideal for the industry, and unlike voluntary standards, companies cannot opt out of government-enforced regulations.

The heightened scrutiny of ESG means that any ESG effort must be approached with great care and sensitivity toward antitrust. Trade organizations can be alleged to be conduits for sharing sensitive information, and statements about intentions to adhere to policies or standards can be interpreted as signals or invitations to collude, even when made publicly. Accordingly, the compliance rules applicable to trade associations and public announcements of intentions should be observed diligently when the topic is ESG.

Conclusion: A Case to Watch

Finally, while ESG aspirations have not yet been tested as a defense to antitrust claims, there is no basis in antitrust law for targeting ESG goals as inherently suspect or deserving of greater antitrust scrutiny than other industry self-regulatory efforts. Given the controversial nature of ESG, this case will certainly be followed closely.

The GIR 100, a definitive guide to the world’s top firms for investigations, recognized Cohen & Gresser for its exceptional representation of high-profile individuals and companies. The firm was highlighted for its strong team of renowned lawyers operating in key jurisdictions worldwide. The GIR 100 is based on comprehensive submissions and rigorous independent research, identifying the top 100 firms globally that excel in government-led, internal, and cross-border investigations.

Cohen & Gresser’s White Collar Defense and Regulation practice, which spans its offices in New York, Washington, D.C., Paris, and London, is central to its continued success. The practice boasts a highly experienced Internal Investigations team that advises global clients, including corporations, boards of directors, special committees, and audit committees.

The team’s work encompasses the full spectrum of investigations, from responding to discrete, anonymous employee complaints to managing complex, wide-ranging investigations tied to ongoing litigation or regulatory and criminal scrutiny.

This recognition underscores Cohen & Gresser’s dedication to providing clients with sophisticated, strategic counsel in even the most challenging investigative matters.

Vault praises C&G for its “White Collar Whizzes,” emphasizing the firm’s “strong reputation in this area.” The publication also recognizes the firm’s “bustling litigation practice,” noting its expertise in handling a broad range of matters, including “antitrust and bankruptcy, class actions and commercial litigation, directors and officers liability, products liability—and more.”

In addition to this recognition, Vault also named C&G on numerous quality-of-life lists, including Best Midsize Law Firms for Pro Bono, Best Midsize Law Firms for Firm Culture, Most Selective Midsize Law Firms, and Best Midsize Law Firms for Wellness.

Vault created the Top 150 Under 150 list to recognize outstanding small and midsize law firms that deliver big results. Vault editorial and research teams evaluated survey data, news stories, trade journals, and other legal publications; spoke with lawyers in the field; and reviewed other published rankings. Editors also assessed each firm for prestige, quality of life, and professional growth opportunities and then narrowed down the results to come up with the final list of recognized law firms.

RPA enforcement, however, seems to be making a comeback. Antitrust enforcement under the Biden Administration has largely rejected the “consumer welfare standard”—which equates competition with harm to consumers, typically in the form of increased prices—in favor of a broader focus on excessive consolidation of private power and its longer-term economic implications. The RPA, enacted to protect smaller retailers from a competitive advantage that benefited chain stores and other larger competitors able to obtain lower wholesale prices, is consistent with this approach.

Recent press reports suggest the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) may be on the verge of an RPA enforcement action. These reports follow public statements by both FTC Chair Lina Khan and Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya emphasizing the RPA and indications that the FTC has opened at least two RPA investigations under Khan’s leadership. In March 2024, a group of 16 lawmakers, including some of the most prominent supporters of the Biden Administration’s enforcement agenda, urged the FTC to “revive enforcement” of the RPA in connection with consolidation and high prices in the food industry.

Moreover, the RPA remains enforceable through private actions. While such actions have been rare, and successful actions even more so, a federal court in California last month affirmed a jury verdict in favor of wholesalers of eye drops against distributors who were found to have sold the drops to Costco and Sam’s Club at a lower price than the plaintiffs received. In addition to the jury’s damages award, the court granted injunctive relief. L.A. Int’l Corp. v. Prestige Brands Holdings, Inc., 2024 WL 2272384 (C.D. Cal. May 20, 2024). Revived agency enforcement would likely lead to an increase in private actions as well.

Accordingly, businesses that sell and purchase goods should be familiar with the key provisions of the RPA:

- The RPA prohibits discrimination in price between at least two consummated sales to different purchasers. Mere offers to sell at a particular price or refusals to sell at all to a particular purchaser do not trigger RPA liability. Moreover, the RPA is limited to “commodities,” i.e., tangible goods sold for use, consumption, or resale within the United States. Services are excluded from the RPA’s ambit.

- The two sales must be reasonably contemporaneous, and the goods involved must be of “like grade and quality.”

- At least one of the sales must be in interstate commerce, i.e., across state lines.

- Prohibited discrimination includes the furnishing of services or facilities in connection with the sale of the commodity; any such services or facilities must be made available to all purchasers on proportionally equal terms. If a seller compensates its customer for services or facilities furnished in connection with the sale, such as marketing or promotion, it must make those payments available on proportionally equal terms to other purchasers that compete to distribute the same product.

- However, the RPA does not prohibit price differentials that merely allow for the differing methods or quantities in which the goods are sold or delivered to the respective purchasers or that result from a response to changing conditions affecting the saleability of goods (such as deterioration of perishable goods or obsolescence of seasonal goods).

- And there is no actionable price discrimination if the lower price was functionally available to the disfavored purchaser, provided that the disfavored purchaser was aware of the availability of the lower price and that such availability was not merely theoretical. For example, a volume-based discount might be facially available to all customers, but if the requisite volume threshold is higher than certain purchasers can realistically meet, it may not be considered functionally available to all purchasers.

- Unlike other antitrust statutes, the RPA does not require a showing of marketwide injury to competition. Rather, it is sufficient to show that the discrimination harmed a company’s ability to compete with the grantor of the discriminatory price, any person who knowingly received the benefit of the discriminatory price, or with customers of either. While the competitive injury ordinarily will occur at the buyer’s level, the RPA also permits claims for harm to competition between sellers, between customers of the favored and disfavored purchasers, or between customers even further downstream.

- A seller who is alleged to have discriminated in violation of the RPA may establish, as an affirmative defense, that it granted a lower price to the favored purchaser in order to meet (but not beat) the price of a competitor.

- Liability is not limited to sellers; the RPA also imposes liability on purchasers who knowingly induce or receive a favorably discriminatory price.

- A standalone provision of the RPA prohibits parties to a sale from granting or receiving any compensation, or any allowance or discount in lieu of compensation, except for services rendered.

The RPA is an oft-overlooked component of antitrust compliance, largely due to its infrequent enforcement. However, every company’s antitrust compliance program should include a review of its relationships with customers and suppliers to ensure that its pricing plans and pricing decisions comply with the RPA and that the reasons for any deviations from price, such as meeting competition, are well documented.

Mark Cohen is once again recognized as a Leading Partner in both Securities Litigation and Corporate Investigations & White-Collar Crime: Advice to Individuals.

The 2024 guide also recognizes Lawrence T. Gresser, Jonathan Abernethy, Jason Brown, S. Gale Dick, Christian Everdell, Jeffrey Lang, Alisa Lu, Melissa Maxman, Douglas Pepe, John Roberti, Daniel Tabak, and Ronald Wick as recommended lawyers.

This 17th edition of The Legal 500 United States guide, which identifies the “true superstars of the profession,” involved a detailed assessment of various factors, including work conducted by law firms over the past 12 months and historically; experience and depth of teams; and client feedback.

Founded in 2002, Cohen & Gresser’s New York office serves as the firm’s headquarters. Our New York attorneys are particularly strong in complex litigation, investigations, and transactions. The firm’s Washington, D.C. office handles a range of commercial litigation and regulatory enforcement actions, with a focus on domestic and foreign antitrust issues.

View All

General Inquiries

info@cohengresser.comManaging Partner

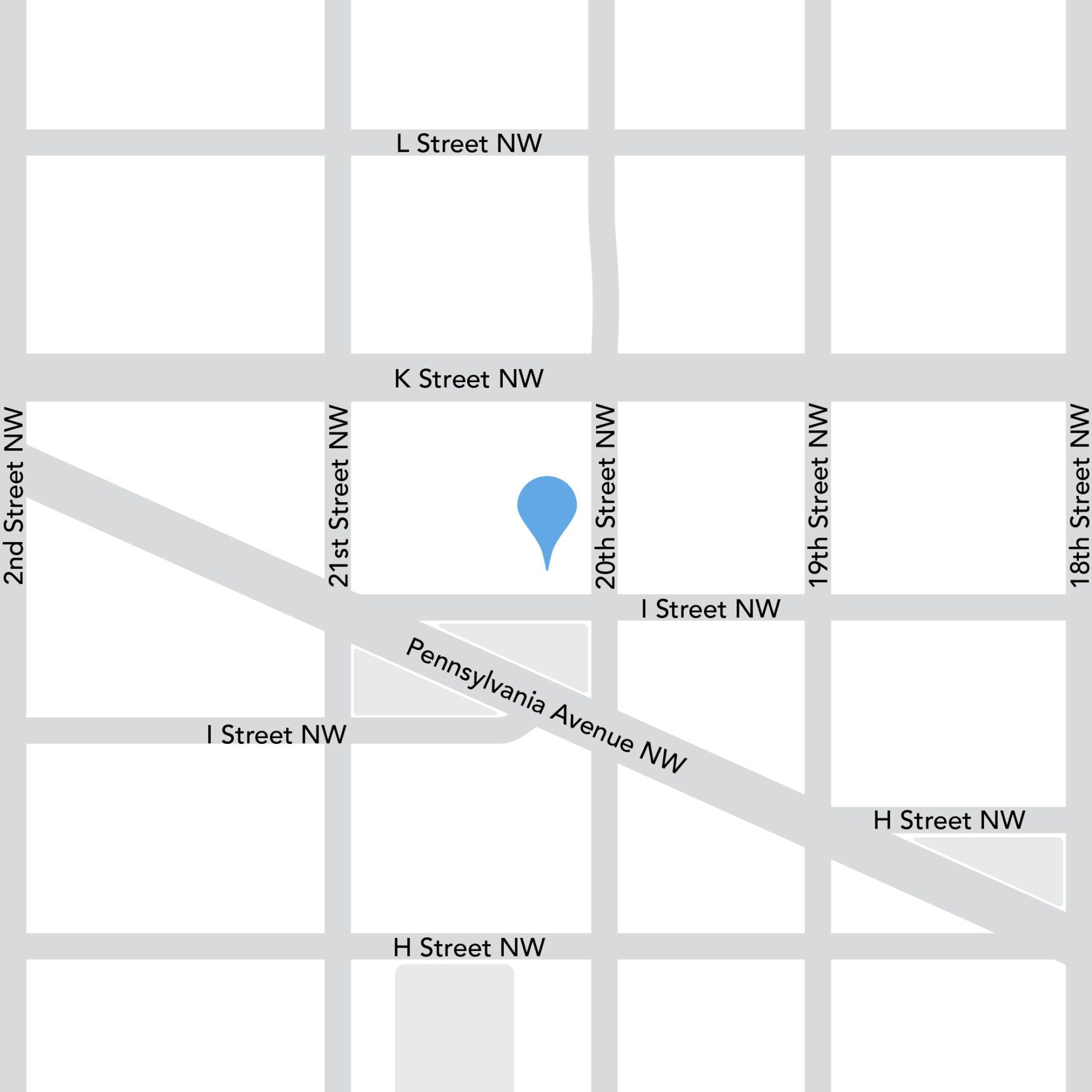

Melissa H. Maxman2001 Pennsylvania Ave, NW

Suite 300

Washington, D.C. 20006

+1 202 851 2070 phone

+1 202 851 2081 fax